physics

The nature of consciousness is a unique mystery among all the mysteries of science. Neuroscientists can not simply give a fundamental explanation of how it comes from the physical states of the brain – we are not even sure that we will ever be able to explain it. Astronomers are interested in the fact that there is dark matter, geologists are looking for the sources of life, biologists are trying to understand the cancer – and this is all, of course, difficult tasks, but at least we more or less imagine in which direction we need to dig, and we There are rough concepts of how their decisions should look. And our own “I”, on the other hand, lies outside the traditional scientific methods. Following the philosopher David Chalmers, we call it “a difficult problem of consciousness.”

But, perhaps, consciousness is not one such unique task in complexity. The philosophers of science, Gottfried Leibniz and Immanuel Kant, fought not with such a well-known, but with as complex a task as matter. What is physical matter, in fact, if we ignore the mathematical structures described by physics? And this problem, apparently, lies beyond the limits of traditional scientific methods, since we can only observe the impact of matter, but not its essence – the “PO” of the universe, but not its “iron.” At first glance these problems seem completely separate. But if you look closely, it turns out that they are deeply connected.

Consciousness is a multifaceted phenomenon, but subjective perception is its most amazing aspect. Our brain does not just collect and process information. In it, not only biochemical processes take place. He creates a bright series of feelings and sensations, for example, a kind of red color, a feeling of hunger, surprise from philosophy. You are yourself, and no one else can recognize this sensation as directly.

Our consciousness includes a complex set of sensations, emotions, desires and thoughts. But in principle, the sensations of consciousness can be very simple. An animal that feels pain or an instinctive urge, without even thinking about it, still has a mind. Our consciousness, too, is always aware of something all the time – it thinks about the objects of the world, abstract ideas, about oneself. But even he who sleeps and sees incoherent sleep or hallucinates will still have consciousness in the sense of having a subjective experience, even though he does not realize anything concrete.

Where does consciousness come from in this, most general, Sense? Modern science gives us reasons to believe that our consciousness grows from physics and chemistry of the brain, and not from something non-material and transcendental. To obtain a conscious system, we need only physical matter. Collect it in the right way, in the form of a brain, and consciousness will appear. But how and why consciousness can appear because of some kind of collected matter, initially unconscious?

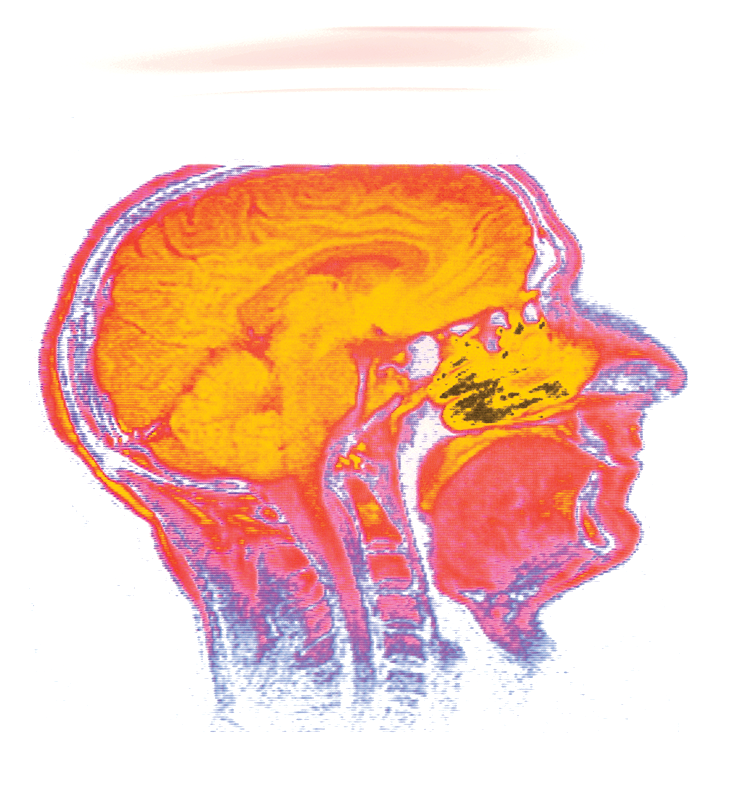

The problem is difficult because its solution can not be described by experiment and observations. Through increasingly complex experiments and advanced imaging technologies, neuroscience gives us more and more detailed patterns of what consciousness feels, depending on the physical states of the brain. Neuroscience may be able to tell us someday what all our conscious states of the brain have in common: for example, they all have high levels of integrated information (as in “ Integrated Information Theory” from Giulio Tononi) that they They spread messages in the brain (as in Theory of the Global Workspace by Bernard Barse), or that they create oscillations at a frequency of 40 Hz (as suggested by Francis Crick and Christoph Koch). But all these theories have a difficult problem. How and why does the system integrating information propagating messages or oscillating with a frequency of 40 Hz feel pain or joy? The emergence of consciousness from simple physical complexity seems equally enigmatic, no matter what form this complexity takes.

And, it seems, the discovery of specific biochemical, and as a result, the physical details underlying these complexities, Nothing will help us. It does not matter how accurately we describe the mechanisms underlying, for example, sensations and recognition of tomatoes, we can still ask: why is this process accompanied by a sensation of red, or any other? Why can not the physical process be carried out without consciousness?

Other natural phenomena, from dark matter to life, albeit mysterious, do not seem so unsolvable. In principle, we can accept that for their understanding we need only collect more physical details: build the best telescopes and other instruments, develop better experiments, notice new laws and patterns in the data already available. If we suddenly got knowledge about all the physical details and laws of the universe, these problems would have to disappear. They would have gone the same way as the problem of heredity disappeared after the discovery of the physical aspects of DNA. But the difficult problem of consciousness remains, even in the presence of knowledge of all conceivable physical aspects.

In this sense, the deep nature of consciousness lies outside scientific possibilities. But at the same time we believe that physics in principle can tell us everything about the nature of physical matter. Physicists tell us that matter is created from particles and fields that have properties such as mass, energy, charge, spin. Physicists could not yet open all the fundamental properties of matter, but they are approaching this.

But there is reason to believe that matter is something more than physics tells us. Physics, in general, tells us what fundamental particles do or how they are related to other things, but nothing about what they themselves represent, regardless of everything else.

For example, the charge is The property of repelling other particles with the same charge and attracting particles with the opposite charge. In other words, charge is a way of dealing with other particles. Similarly, mass is a property of reacting to applied forces and gravitational attraction of other particles with a mass that can be described as a curvature of space-time or interaction with the Higgs field. There are also other things that make particles, and the ways in which they are related to other particles and with space-time.

In general, it seems that all the fundamental physical properties can be described mathematically. Galileo, the father of modern science, once said that the book of nature is written in the language of mathematics. But mathematics is a language with clear limitations. It can describe only abstract structures and connections. For example, we only know about numbers how they relate to other numbers and other mathematical objects-that is, what they “do”, the rules they follow when adding, multiplying, etc. Similarly, we know the properties of a geometric object, such as a graph node, in its relation to other nodes. In the same way, purely mathematical physics can tell us only about the relationships of physical entities and the rules governing their behavior.

One may wonder what physical particles are, regardless of what they do or how they are related to Other things. What are physical entities in themselves, what properties are inherent in them? Some argue that particles are only expressed through their relationship with each other, but intuition rebels against such statements. For the relationship, it is necessary to have two things that have relationships with each other. Otherwise, this attitude is empty – a performance without actors, a lock from the air. In other words, the physical structure must be realized or executed from a certain substance or substance, which in itself is not an empty structure. Otherwise, there will be no difference between the physical and mathematical structure, between the tangible universe and the abstraction. But what is this substance that realizes the physical structure, and what are its internal, non-structural properties that describe it? This problem is a close relative of Kant’s classic problem concerning things in themselves. The philosopher Galen Strawson calls it “a difficult problem of matter.”

Here there is irony, because we usually imagine physics as a science that describes the “iron” of the universe – real, concrete things. But in fact, physical matter (at least, those aspects of it that physics tells us about) is more like a software: a logical and mathematical structure. According to the difficult problem of matter, this software requires iron for work. Physicists brilliantly carried out the reverse engineering of the algorithms – or of the source code – of the universe, but excluded the specific implementation.

The difficult problem of matter differs from other problems of interpretation of physics. Modern physics gives us riddles of the type: how can matter at the same time resemble a particle and a wave? What is the collapse of the quantum wave function? What is more fundamental, continuous fields or individual particles? But all these are questions of how to properly understand the structure of reality. A difficult problem of matter would appear, even if we had answers to all questions about the structure. Regardless of what structures we speak of, from the most strange and unusual to the most intuitive ones, the question will arise: how they are realized not from a purely structural point of view.

Such a problem appears even in Newtonian physics describing Structure of reality on a simple intuitive level. Roughly speaking, Newtonian physics says that matter consists of solid particles interacting either through a collision or through gravitational attraction. But what is the intrinsic nature of a substance behaving so simply and intuitively? What is the iron on which the software of the Newton equations is implemented? Someone may decide that the answer is simple: it is realized by means of solid particles. But hardness is behavior coming from particles that resist penetration of other particles and overlapping each other – that is, in fact, another relationship with other particles in space. The difficult problem of matter arises with any structural description of reality, regardless of its quality and intuition.

Just as a difficult problem of consciousness, the difficult problem of matter can not be solved through experiments and observations, or through the collection of additional physical details. They just show us more structures – at least as long as physics remains a discipline dedicated to describing reality through mathematics.

Could a difficult problem of consciousness and a difficult problem of matter be connected? In physics, there is already a tradition of combining problems of physics and problems of consciousness, for example, in quantum theories of consciousness. Such theories are often belittled because of their false conclusions about the fact that if quantum physics and consciousness are mysterious, then their crossing will somehow become less mysterious. The idea of linking a difficult problem of consciousness with a difficult problem of matter can be criticized on the same basis. But if you look closely, these two problems complement each other at a deeper and more specific level. One of the first philosophers who noticed this connection was Leibniz at the end of the 17th century, but Bertrand Russell formulated the exact modern version of the idea. Modern philosophers, including Chalmers and Strawson, re-discovered this connection. It is described as follows:

The difficult problem of matter requires finding non-structural properties, and consciousness is a phenomenon that can satisfy these requirements. The mind is full of quality properties, from the redness of red color and the discomfort of hunger to the phenomenology of thoughts. Such experiences, or “qualia,” may have an internal structure, but they have something else besides the structure. We know something about the essence and internal properties of sensations, about what they are themselves, and not just how they work and how they are related to other properties.

For example, imagine a person, Never seen red objects and never heard of the existence of red. He does not know anything about how “redness” is related to the states of the brain, to physical objects like tomatoes or to the wavelength, or how it is related to other colors (for example, similar to orange, but very different from green ). And one day he had a big red stain in his hallucinations. Apparently, a person after that learns that there is redness, although he knows nothing about her connections with other things. The knowledge obtained by him will be knowledge without relations, knowledge of what redness itself is.

From this it follows that consciousness in a primitive-rudimentary form is an “iron” on which the “software” described by physicists works . The physical world can be perceived as a structure of conscious sensations. Our own feelings realize the physical connections that make up our brain. Some simple, elementary forms of sensations realize the connections that make up the fundamental particles. Let us take an electron. Electron attracts, repels, and somehow relates to other entities in accordance with fundamental physical equations. What makes up his behavior can be imagined as a stream of tiny sensations of an electron. Electrons and other particles can be thought of as mental beings with physical abilities; As the streams of sensations that are in physical relationship with other streams of sensations.

This idea may seem strange and even mystical, but it is born from careful reflection on the limitations of science . Leibniz and Russell were scientific rationalists – what proof their immortal contributions to physics, logic and mathematics serve – but just as deeply they were devoted to the reality and uniqueness of consciousness. They concluded that to pay homage to both phenomena, it is necessary to radically change thinking.

And this is really a radical change. Philosophers and neuroscientists often imagine a consciousness in the form of software, and the brain – in the form of “iron.” This assumption turns it upside down. If you look at what physics says about the brain, it will, in fact, be a software – a purely set of relationships – to the lowest levels. And consciousness is actually more like iron, because its properties are qualitative, not structural. Therefore, conscious experiences can just be what structure is the physical structure.

If to solve thus the difficult problem of matter, the difficult problem of consciousness disappears by itself. There are no questions about how consciousness arises from a matter that has no consciousness, since all matter is inherently conscious. There are no questions about the dependence of consciousness on matter, since it is matter that depends on consciousness – just as the relationship depends on the members entering into these relationships, and the structure depends on the implementer, the software working on the iron.

One can argue that this is pure anthropomorphism, an unjustified mapping of human properties onto natural phenomena. Where did we get that the physical structure requires some internal implementers? Is it because our brain has internal, conscious properties, and we are used to thinking about nature in terms we know? But this objection can be refuted. The idea that internal properties are needed in order to distinguish real concrete things from abstract structures has nothing to do with consciousness. Moreover, the accusation of anthropomorphism can be refuted by counter-charging in human exclusivity. If the brain is completely material, why should it differ from the rest of the matter in terms of inherent intrinsic properties?

This viewpoint, about underlying consciousness, is called differently, but one of the most suitable names is “Two-faceted theory of consciousness” or “two-way monism”. Monism contrasts with dualism, which says that consciousness and matter are fundamentally different substances or types of things. Dualism is considered scientifically unfounded, as science does not demonstrate any evidence of the presence of nonphysical forces affecting the brain.

Monism argues that all reality is made from the same substance. It can be of different types. The most common monistic view is physicalism (also known as materialism), postulating that everything consists of a physical substance possessing only one aspect described by physics. Today, this view is generally accepted among philosophers and scientists. According to physicalism, a complete and purely physical description of reality does not miss anything. But according to the difficult problem of consciousness, any purely physical description of a conscious system, for example, of the brain, at first glance, still misses something. Оно не может полностью описать, что означает быть такой системой. Она, можно сказать, описывает объективные, но не субъективные аспекты сознания: работу мозга, но не нашу внутреннюю разумную жизнь.

Двухаспектный монизм Рассела пытается заполнить этот дефицит. Он принимает точку зрения на мозг как на материальную систему, ведущую себя в соответствии с законами физики. Но он добавляет ещё один внутренний аспект к материи, спрятанный от внешней точки зрения физики, который нельзя определить никаким чисто физическим описанием. Но, хотя этот внутренний аспект не поддаётся физическим теориям, он поддаётся нашему внутреннему наблюдению. Наше сознание и составляет этот внутренний аспект мозга, и это наш ключ к внутреннему аспекту других физических вещей. Перефразируя лаконичный ответ Артур Шопенгауэра Канту: мы можем осознавать вещь в себе, потому что мы ею являемся.

Двухаспектный монизм бывает умеренным и радикальным. Умеренные версии утверждают, что внутренний аспект материи состоит из т.н. протосознания или «нейтральных» свойств: свойств, неизвестных науке, но отличающихся от сознания. Природа таких ни сознательных, ни физических свойств, кажется довольно загадочной. Как и упомянутые ранее квантовые теории сознания, умеренный двухаспектный монизм можно обвинить в простом добавлении одной загадки к другой, в ожидании, что они взаимно уничтожатся.

Самый радикальный вариант двухаспектного монизма утверждает, что внутренний аспект реальности состоит непосредственно из сознания. Это, разумеется, не то же самое, что утверждает субъективный идеализм, говорящий о том, что физический мир – это не более, чем структура, живущая в человеческом сознании, и что внешний мир – в каком-то смысле иллюзия. Согласно двухаспектному монизму, внешний мир существует независимо от человеческого сознания. Но он не существовал бы независимо от любого типа сознания, поскольку все физические вещи связаны с некоей формой присущего им сознания, их собственного внутреннего реализатора, или «железа».

В качестве решения трудной проблемы сознания двухаспектный монизм сам сталкивается с возражениями. Самое частое из них – то, что из него следует панпсихизм, представление о всеобщей одушевлённости природы. Критики считают маловероятным наличие сознания у фундаментальных частиц. К этой идее действительно приходится привыкать. Но давайте рассмотрим альтернативы. Дуализм выглядит невозможным с точки зрения науки. Физикализм принимает, что объективный, научно обоснованный аспект реальности – и есть вся реальность, из чего следует, что субъективный аспект сознания – это иллюзия. Возможно – но не должны ли мы быть больше уверены в том, что у нас есть сознание, чем в том, что у частиц его нет?

Второе важное возражение – т.н. проблема комбинации. Как и почему сложное и объединённое сознание в нашем мозге появляется из-за создания структуры из частиц с простым сознанием? Этот вопрос выглядит подозрительно похожим на изначальную проблему. Я вместе с другими защитниками панпсихизма утверждаем, что проблема комбинации уже не такая сложная как изначальная трудная проблема. В некоторых смыслах легче понять, как перейти от одной формы сознания (набора разумных частиц) к другой (разумному мозгу), чем то, как перейти от неразумной материи к разумной. Многие же считают это неубедительным. Возможно, это лишь вопрос времени. Над исходной трудной проблемой, в какой-либо её форме, философы задумывались столетиями. Проблема комбинации не так известна, что оставляет надежду на появление незамеченного ранее решения.

Возможность того, что сознание – реальный и конкретный аспект реальности, фундаментальное «железо», позволяющее работать «софту» наших физических теорий, представляет собой радикальную идею. Она полностью выворачивает наше обычное представление о реальности, и такое представление довольно сложно воспринять. Но она может решить две труднейших проблемы науки и философии разом.