symmetrical

We bring to your attention the five most symmetrical objects ever created by man, and an explanation of why they are so hard to create.

Quartz rotor of a gyro For Gravity Probe B

In 2004, the American space mission Gravity Probe B (GP-B) was launched into space on a Delta II rocket. She had to test the general theory of relativity. On the satellite in the Earth’s orbit, among other things, there was a set of gyroscopes capable of measuring two phenomena predicted by GR: the curvature of space-time (geodesic precession) and the curvature of space-time by large objects (entrainment of inertial frames of reference). To measure these phenomena gyroscopes had to be incredibly accurate. A mistake greater than one hundred billionth of a degree per hour would spoil the experiment. The accuracy of standard gyroscopes used on submarines and military aircraft is 10 million times worse.

For the construction of such precise gyroscopes, it was necessary to create perfectly symmetric rotors, rapidly rotating elements, allowing the gyroscopes to maintain their position in space. They had to be perfectly balanced and homogeneous. The GP-B team made these small spheres from pure quartz blocks grown in Brazil and baked in Germany. The surface of each gyroscope is almost perfectly spherical, and differs from the sphere by no more than ten millionth of a centimeter.

According to the Guinness Book of Records, these are the most round objects ever created. The Stanford team that worked on them claims that only neutron stars are more spherical.

The only real competitor GP-B in the field of ideal spheres, this is a ball, which will soon determine the kilogram. This area is the result of the work of the Avogadro project, in which only the cost of raw materials exceeded one million dollars. The goal is to surpass and replace the international prototype kilogram (IPK). Kilogram is the last unit of measurement in the international system of units (metric), still determined by the physical object – the cylinder of the alloy of platinum and iridium – and not by physical principles. This cylinder is under three enclosed glass caps in a temperature-controlled storage located near Paris.

The problem is that the current IPK has lost a bit in weight, compared to 40 similar cylinders, stored in other countries – and this is a serious drawback of the object, designed to determine the mass. In the Avogadro project, two small spheres of almost perfect shape were created, entirely consisting of silicon-28, which should almost always maintain a weight of exactly one kilogram. Silicon-28, used in the spheres, was previously cleaned in Russian centrifuges, which once produced nuclear weapons. Purified silicon was sent to Germany, and crystals were grown there.

The final sphere differs from the ideal one by no more than 25 nm, and most likely will soon replace the sphere with the GP-B from the first place. “If our spheres were the size of the Earth, then the irregularities on them would be in the size of 12 to 15 mm, and from the sphere they would differ only by 3-5 m,” said chief optician Achim Leistner, from the Australian State Association Scientific and applied research.

Spheres are ready, and now researchers from different countries will try to calculate the exact number of atoms contained in them in order to work out a universal agreement on what is the mass of one kilogram

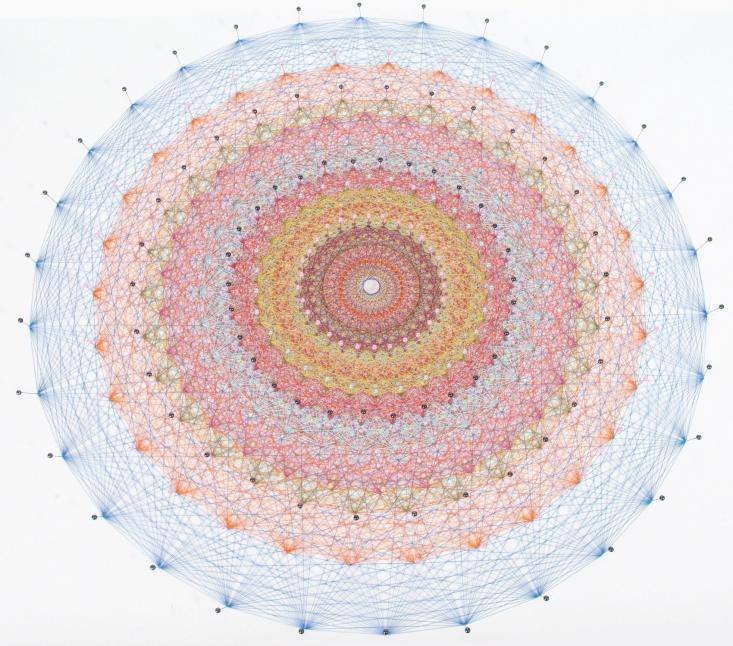

Group Lee E8

Without burdening themselves with the annoying properties of the physical world, mathematicians can imagine unrealistically symmetrical structures. For example, the Lie group E8 is a set of 248 different forms of symmetry applicable to the theoretical 57-dimensional object. The structure was invented at the end of the XIX century, but only recently researchers from Britain and Germany announced the creation of a physical system representing E8 in the real world.

Embroidery based on computer image

To see the symmetry of E8, the researchers cooled the crystal from cobalt and niobium to temperatures close to absolute zero. Then they placed the crystal in a magnetic field, and with increasing its strength, the spins of electrons inside the crystal began to line up according to the structure of E8. The observation of this symmetry not only speaks of the possibility of creating very symmetric systems-it also says that in the quantum world there are hidden symmetries that determine the self-organization of electrons.

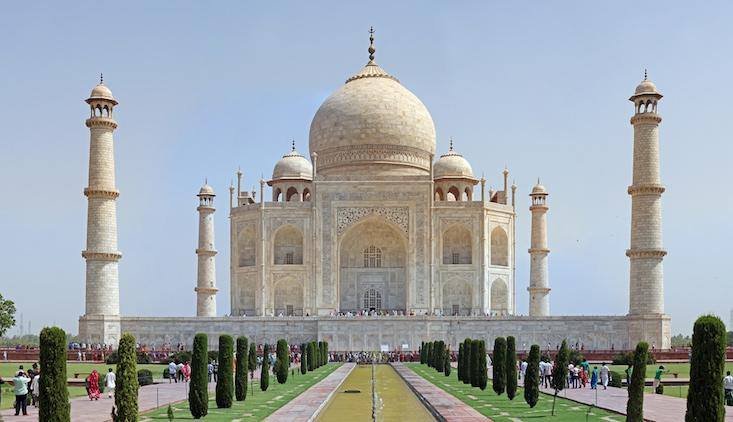

The Taj Mahal

Most people will never encounter a sphere GP-B or with a kilogram of silicon-28. But they can see a surprisingly symmetrical structure by visiting India. The Taj Mahal was built by the Padishah Shah Jahan as a mausoleum in memory of his wife Mumtaz-Mahal, who died during the birth of the 14th child. Jahan wanted the building to represent a harmonious relationship, and asked the architect to portray something two-sided-symmetrical. As a result, a structure is obtained in which symmetrical details are encountered from large plans to decorative elements.

The Taj Mahal is often called the key example of symmetry in structures, but it is difficult to determine which Of the buildings ever built was perfectly symmetrical, as many architects used symmetry in their designs. For many years, mathematics and architecture have been one discipline, and architects have valued buildings that look just like their reflection.

Obsidian ear tunnels

To create something man-made and at the same time very symmetrical is difficult even with the current development of technology. Therefore, the discovery of these surprisingly symmetrical ear jewelery, attributed to the age of hundreds of years, has so excited fans of conspiracy, claiming that in principle they could not be done without modern tools. Archaeologists do not agree with this. These gags are really made amazingly skillfully, but they were made not by aliens and not by jokers on modern machines – but by particularly skilled Aztecs. Archaeologists, detached and workshops, where they were made, say that many of them were made with the help of stone, ceramics and wooden tools.

“It’s amazing not only that they were created with such art and precision, but also that they lived to this day without being crushed,” says John Milhauser [John Millhauser]an anthropologist from the State University of North Carolina, who found similar tunnels in the city of Xaltokan, north of Mexico City. So, even if they look supernatural, they really just serve as an example of amazing craftsmanship.